On 1 October, 2022, we sounded the alarm on the possibility of a banking crisis. Just three days prior, we had published our November Outlook with an ominous subtitle: "September: Banking troubles loom (large)”. In it, we wrote:

The drastic action of the Bank of England to start to buy U.K. long-term bonds (Gilts) to halt the meltdown of pension funds and most likely other financial institutions can be considered a sign of things to come. Central banks will face the option of fighting inflation vs. utter financial mayhem. We probably know what they will choose, but the big question is, will they be able to stop the approaching banking panic? We are not so sure, but they will most likely try.

Programs of quantitative tightening (QT), that is, the asset roll-off of central banks were suppressing market liquidity, while the Russo-Ukrainian war, the energy crisis and fears of the close proximity of a recession were weighting sentiment among investors. It’s thus no wonder that the highly levered, deeply indebted and fragile financial system almost imploded. Then, during October, the Swiss National Bank, the Federal Reserve and the Saudi National Bank organized a bailout of Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse. A financial crisis was averted, again.

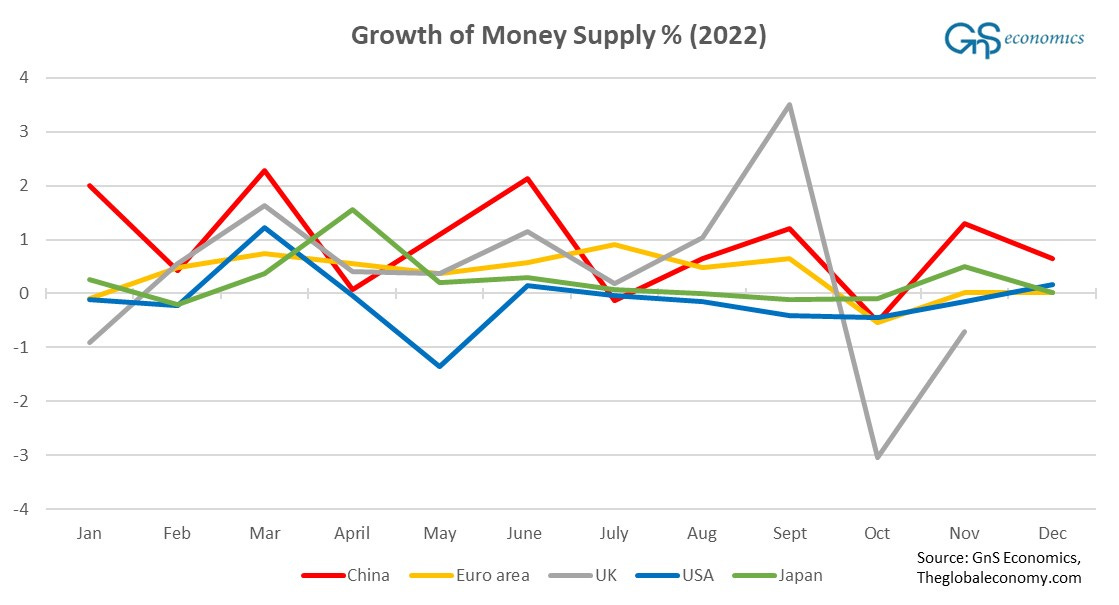

The sudden disappearance of market liquidity in October can be depicted with the drastic decline of the supply of money of the five largest economies/areas. Between September and October, 2022, the world economy suddenly lost over $500 billion worth of liquidity (money), which is the biggest drop on record (since 2000). No wonder the financial system almost crumbled. November, on the other hand, saw an nearly matching increase.

So, what happened after October? QT is still very much ongoing, but markets have held up. Why?

It turns out that this is the result of the ‘sorcery’, or alchemy, of central bankers with one major player currently deciding the fate of the global financial system.

Where do you run when the wolves come?

Central bankers have at their disposal a wide range of tools to, effectively, distort the functioning of the financial system. These naturally include their ability to alter the interest rates banks charge in their borrowing (deposit-taking) and lending activity by setting interest rates of central bank reserves. After the Panic of 2008 central banks also started to alter long-term interest rates more directly through buying of government bonds (QE). This led to the ‘everything bubble’ in the asset markets.

The first effort to diminish the global balance sheet of central banks ended with the implosion of the repurchase (repo) markets of the U.S. in September 2019. This caused an existential crisis for the U.S. and global financial system, as the $4 trillion repo-markets are the ‘financial plumbing’ of the U.S. providing short-term liquidity to a wide variety of financial institutions.

The crisis came to be after major U.S. ‘primary dealer’ banks suddenly refused to lend to other counterparties in the repo-market on the 17th September 2019. We published our extensive analysis on the crisis on 14 December 2019. We wrote:

QE accustomed banks to holding large amounts of excess reserves, which provided a reliable source of interest income. When QT started to reduce reserves, they replaced them with another reliable source, Treasuries, which acted as a hedge on their balance sheet against riskier lending practices and securities holdings induced by QE programs. Obtaining a hedge against riskier assets and loans (loan portfolios in particular take a long time to adjust) becomes especially important, if the economic outlook is expected to worsen—as it is presently.

This leads us to another and potentially more worrying development: increased access to the repo-market by hedge funds to increase their leverage. They seem to have been getting short-term funding from the repo-market to buy U.S. T-bills, which they have then re-invested in the repo-market to obtain more short-term funding to buy T-bills, etc. Using this “leverage-loop” they have been able amass very high leverage ratios.

The behavior of hedge funds is also the end-result of massive central bank interference in the global capital markets. When the yields of practically every financial asset class are squeezed to near-zero (or less!) due to artificial liquidity from the central banks, leverage becomes the only way to obtain yield sufficient for fixed-income investors.

The asset-purchase (QE) programs have altered the financial system in many ways, leading to all kinds of “perversions”, high leverage and excessive risk taking. QT is an effort to reverse the effects, but in the financial system such actions cannot be reversed without considerable pain.

After the near-meltdown of the financial system, due to retreating market liquidity and spiking interest rates, at the turn of September/October past year, central banks enacted measures to quell the panic. The BoE stepped back into gilt markets for a while, but there also seems to have been joint actions between central banks.

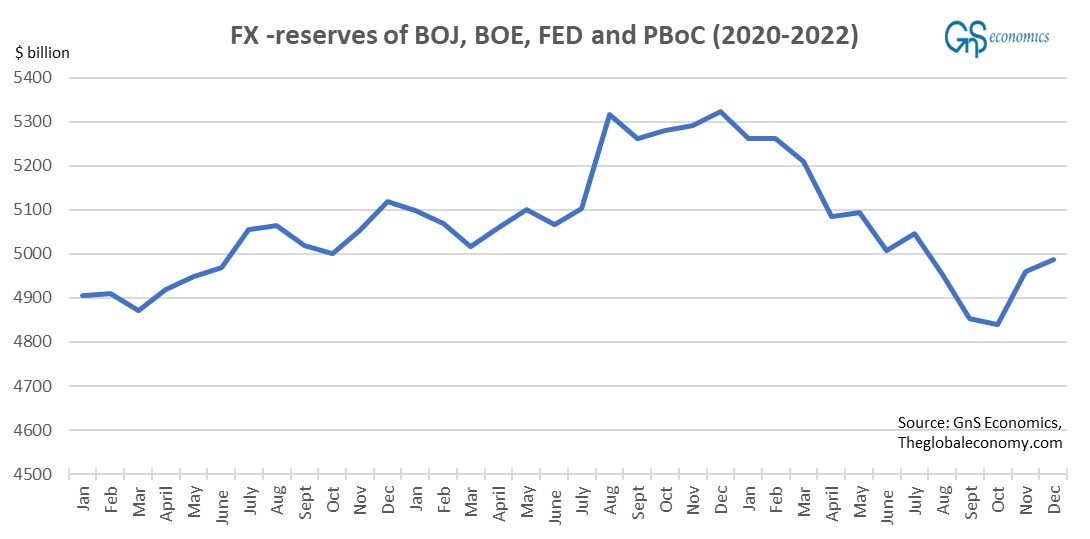

For example, like from a ‘strike of wand’, the Bank of Japan (BoJ), the BoE, the Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) started to increase their foreign exchange (FX) reserves after October. We can only speculate on the actual reason, but the action was synchronous across all major central banks (data from the European Central Bank, ECB, were not yet available).

The foreign exchange reserves can include foreign currencies (including foreign currency swaps), bonds, treasury bills, gold, and other government securities. Whatever the increase of FX-reserves consisted of, they almost surely contributed to the increase in global money supply. They were also most likely agreed as a joint-operation by the central banks to relieve the detrimental effects of QT. However, currently, there’s one player above others.

Enter the dragon (again)

The next figure presents the change in global supply money in billions U.S. dollars in five major industrial countries/areas.

There are three take-aways.

First, China (the PBoC) is dominating the landscape of global money supply. It makes gargantuan supplies and drains of liquidity to and from the global financial system. The September/October crash occurred because the draining of Chinese liquidity coincided with the liquidity-drain of all other central banks.

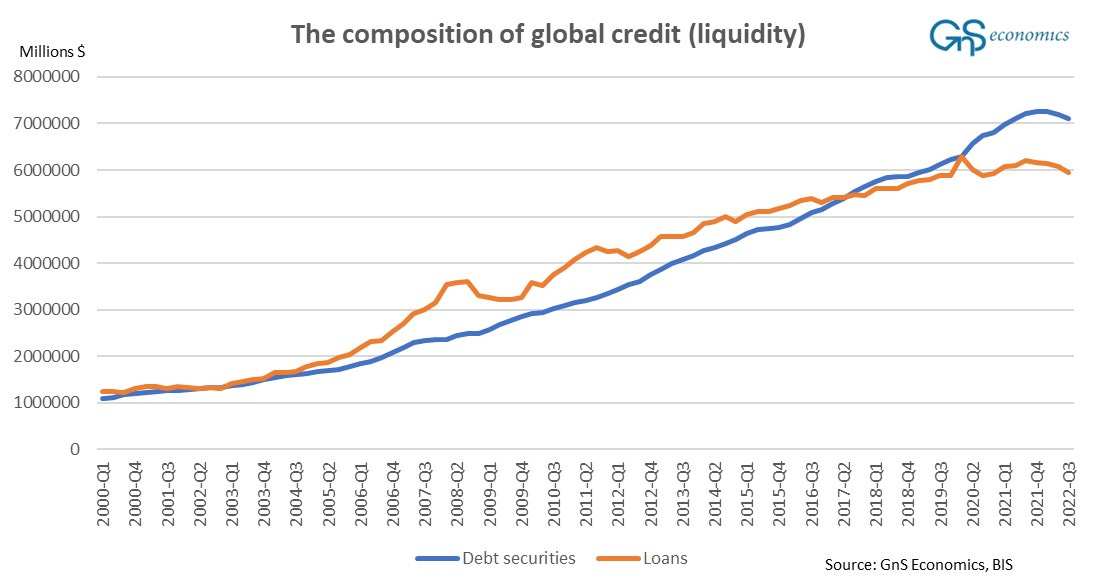

Secondly, QT:s of the Federal Reserve, the ECB and the BoE will continue to drain global money supply making markets more vulnerable to the actions of China, unless they do not constantly increase money through other means, e.g., through swap-agreements or if commercial banks do not match this drain by increasing their lending. As these other means of central banks are de facto temporary and because, e.g., banks in the U.S. are tightening lending standards rapidly and because global lending activity has been in decline (see below), this means that at some point the fate of the global financial system will be subjected to the ‘whims’ of Beijing. That is, we are currently making our financial system highly dependent on the decisions of the PBoC and Chinese leaders.

Thirdly, as the Chinese liquidity-injections seem to be on a declining trend, the financial system may experience a cataclysmic draining of liquidity during the next few months. This would occur in a situation, where the Chinese “draining” would coincidence with a rolling back of the temporary support measures of other central banks and, in the worst-case, with a notable decline in bank lending. We may very well be approaching such a shock.

A cataclysmic collapse is on the horizon

In early 2017, we understood that 1) China saved the world economy from a prolonged recession after 2008 crisis and 2) China has driven the global business cycle ever since. Now, we know that 3) the fate of the global financial system also hangs on the actions of China.

There’s a historical pattern of these Chinese liquidity injections. The major “Spring-draining” of liquidity has occurred in April since 2010. When we add the fact that Chinese debt-stimulus has been fading since October, this implies that we would see another leg down for the markets starting during the latter part of February, which would be likely to escalate into a rout in around mid-March.

There are naturally several factors at play affecting the depth and exact timing of the ‘fall’. We, for example, do not know what the Fed and other central banks will do. That is, we do not know for how long they are going to continue their tempus mensura. The severity of the rout will also be determined by developments in Ukraine.

However, the risk of an outright financial crash will become elevated in the coming weeks and, if it comes to be, there’s also a high risk it will morph into a ‘perfect storm’. Preparation continues to be the key.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

The ECB top brass meeting in Finland just now. Discussing interest rates and inflation. Discussing wartime economy too? I'm afraid famine and energy short supply dominated set of multiple crisis is coming.