Issues contributed:

What are bank runs and how they come to be?

The difference between commercial and shadow banks, and how they contribute to the current crisis.

Credit crunch is getting worse.

Since the start of the current crisis, or its second wave, I have received quite a few inquiries on the banking system. There are so many misconceptions regarding to it that I decided to explain it in more detail in this entry. First, some history.

The foundations of banking practices were developed in Ancient Greece in the harbor city of Piraeus, where the local bankers, or trapezitai, took deposits and provided loans.1 The first known banks that truly resembled modern banks operated in Imperial Rome, which also brought first banking crises. It has actually been said that Rome's financial system was so sophisticated that it was matched only by the banking sector created in during the Industrial Revolution.2

The order of the Knights Templar created a system, where pilgrims could deposit money with the order in Europe and withdraw it in the Holy Land in the 12th century.3 This created a financial system of long-distance remittance. Simple merchant banks, usually in the service of the rulers, appeared to Europe in the 14th century. They were concentrated in financing production and trade of commodities.

The first payment systems resembling the modern ones appeared in the 16th century. They arose from merchant fairs where commodity trades were settled.4 By 1555, the merchant fair of Lyons had become a clearing house for credit and debit balances of merchant houses across the continent. The merchants realized that the trustworthiness of well-known international merchants could be used to pass their I-Owe-Yous (IOU, i.e. a promise to pay back at agreed future) to not so well-known local merchants. This created a credit system, where bilateral promises (IOU:s to pay and receive) between local and international merchants were used as liquid liabilities. These could be assigned from creditor to creditor and, in essence, create money (credit) through building a leverage against the original claim from the well-known merchant. This, basically, created the fractional reserve banking system, where only fraction of money (credit) in circulation holds collateral. This system is at the heart of many banking problems, but essentially the special nature of banks subjects them to runs.

Banking is a business of trust, and it has been broken during the current crisis in a spectacular fashion, as shown by the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, First Republic Bank in the U.S., and with the failure of Credit Suisse in Europe. To understand the failures and the modern banking system, we need to understand who sets their rules, how money is created and how the banking system operates. I will also update the situation with the credit crunch intensifying in the U.S.

The commercial and ‘shadowy’ side of banking

The crises in Europe and the U.S. differ in one crucial aspect (at this point at least). Europe is experiencing something that can be classified as the failure of the investment banking business, while the commercial banking sector is collapsing in the U.S. (explained here). So, to understand the breadth of the crisis, one needs to understand their difference.

The commercial banking sector is the regulated and most commonly known part of the banking sector, where households and firms seek loans and deposits. The shadow banking sector, which investment banks are a part of, is a part of the financial sector that operates outside of, or is only loosely linked to, the traditional system of deposit taking institutions. Many commercial banks, especially the larger ones, also conduct ‘shadow banking activity’.

Commercial banks

The commercial banking system consists of all deposit-taking institutions, which accept retail deposits, that is, they hold deposits especially from households. Commercial banks naturally also extend loans, offer demand and checking deposits, provide savings accounts and basic financial services to households and businesses, usually to small and medium-sized enterprises. This is why they are also more tightly regulated than their 'shadowy' counterparts. The global regulatory arm of commercial banks is the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), which operates under Bank the of International Settlements, or BIS.

BIS is often referred as the "central bank of central banks", as it provides guidance also for central banks. It was founded in 1930, making it the oldest international financial institution. It first acted as trustee and agent for the international loans intended to finalize settlement of the reparations stemming from World War I, which yields its name. It accepts deposits of a portion of the foreign exchange reserves of central banks and invest them prudently to yield a market return.

The BIS also provides a forum for policy discussions and international cooperation among central banks. Therefore, the actual role of the BIS in international finance is quite hidden. Some might even say 'well hidden', because we know very little what goes on in the BIS led discussions between central banks. This quite straight-forwardly implies that there's another layer of secrecy in central bank policies, which is completely out of all democratic control. Some may consider this as a good thing, but it also creates a possibility for invisible corruption in the heart of our financial system. The work of Basel Committee, on the other hand, is rather public, or at least it is regularly reviewed.

Shadow banks

In general terms, the shadow banking sector can be said to consists of all financial entities that provide loans, but are not regulated under the standard banking regulation framework. Basically the shadow banking sector consists of investment banks, structured investment vehicles (SIVs), hedge funds, conduit financial entities setup by banks to fund investments, and money market funds. It plays an important role in the financial world, because as shadow banks can take higher risks than commercial banks, they can provide funding for riskier investment projects than commercial banks. This means that some highly profitable but risky projects that commercial banks are unwilling or unable to finance will be funded through the shadow banks possible creating significant economic gains or even technological breakthroughs.

The flip side of this is that shadow banks are likely to sustain bigger losses than commercial banks from their risky lending activities, especially during economic downturns and recessions. Shadow banks do usually not hold a large capital buffers against losses, which makes them very vulnerably to runs, but also allows them to use higher leverage yielding higher profits. This makes shadow banks more profitable, during economic booms, than their regulated commercial cousins. However, if (when) one of them topples, contagion of mistrust can spread more easily among them than among commercial banks where transparency, though seldom sufficient enough, is greater due to regulation. This was seen, for example, during the GFC 1.0.

Money creation and fractional reserve banking

In modern economies, most money creation occurs in commercial banks. When a person or a company takes a loan, a bank creates a double entry in its balance sheet. One adds the loan to the asset side of the bank and simultaneusly credits a deposit to the borrower's account at the bank. Thus, banks create money “out of thin air” simply by making a loan and making it available to the borrower. When the loan is paid back, the money is "destroyed", and the double-entry in the book-keeping disappears. Naturally, a bank will fund itself by taking deposits also without previously having made a loan to the depositor.

There is a restriction in the money creation by banks. If a bank gives out too many risky loans, loan defaults can lead to substantial losses and even to insolvency bankrupting the bank. If the projects of households and corporations, funded by the loans from banks, turn unprofitable, so will the bank. This means that commercial banks, and money creation, are inherently bound, not just on the riskiness of their loan portfolio, but also on the health of the real economy. Thus, simple accounting rules and rules of the market economy tend to hold the money creation at bay, but it's also restricted through regulation (the Basel Committee) from the government and reserve requirements issued by the central bank. So, banks need to obey the budgetary limit, which is partly set by the economic agents, and partly by the central bank through interest rate decisions and reserve requirements.

In the fractional reserve banking system only a small portion of its liabilities, like deposits, and assets, like loans, are covered by the reserves or the capital of a bank. A bank is an exceptional entity in the sense that while, for example, the output of a tractor company is tractors, the output of a bank is debt.5 This debt is made available to the borrower as a bank deposit (as an IOU). Basically the bank gives a promise that whatever sum you deposit there, you get it back whenever you want. In addition to deposits, this bank debt can be bonds, derivatives or inter-bank funding obtained from inter-bank markets.

What actually are ‘bank runs`?

The problem in fractional reserve banking system is that only a fractional share of this bank debt (or liability) is covered at each point in time by cash of other liquid assets, like central bank reserves and government bonds. So, in practice, a bank run is an over-whelming demand for holders of bank debt (liabilities) to convert it to cash or other liquid forms of assets in excess of the reserves of the bank. Shadow banks also, in practice, operate under the fractional reserve banking, because they usually do not hold large capital buffers against losses. This makes them very vulnerably to runs.

So, in practice, there can be two kinds of bank runs: “normal”, where depositors queue outside of bank offices to obtain cash and/or transfer money from the bank digitally, and '“silent”, where other banks and/or financial institutions cash out from the equity, bonds, derivatives or inter-bank liabilities of a bank. The latter is called ‘silent’, because such a run can only be observed from in-direct sources, like from the fall of the price of the stock or a bond issued by the bank. Both of the types of runs can occur in commercial and shadow banks, but shadow banks are more prone to the ‘silent’ type.

If the run is massive enough, no amount of reserves of the bank or liquidity given by the cental bank can save the bank. A simple way to think of this is through the failure of the SVB, where depositors tried to withdraw over 80% of deposits in a matter of days. Not a single corporation, bank or not, can survive from an onslaught, where its balance sheet shrinks by several tens of percentage points in just days. With normal corporations, such an event is practically impossible without some devastating event, like an earthquake destroying a factory of a firm. However, due to the special nature of a bank, this can occur through normal business transactions (e.g. withdrawals), whose volume just becomes devastating. This also makes the onset of bank runs practically impossible to forecast, because they are inherently driven by psychological factors (fear), even though the banks that are vulnerable to it can be rooted out.

What comes next?

We are in a period, where a bank run from almost any U.S. bank, or many European banks can start practically at any minute. The interesting question is, for how long can the authorities keep up of forcing mergers of failed banks and more stable ones?

This phase can last surprisingly long, because it has already become a ‘new normal’. Market players seem not to care about bank failures anymore possible because they still trust governments and central bans to manage failures so that they will not lead to cascading losses for depositors and investors. So, we are likely to be in a somewhat strange “quiet period”, where bank failures do not create major shifts in the investor sentiment.

However, this is likely to change drastically, when recession arrives, and we are here.

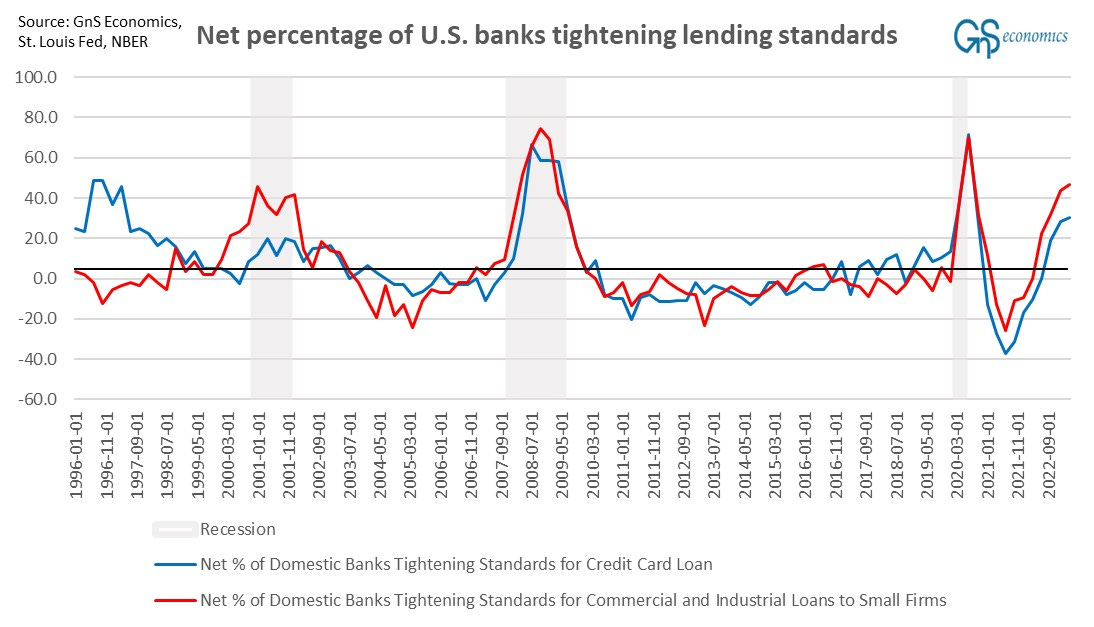

Banks are still tightening credit standards, while the pace seems to have eased a bit. For example, over 40% of banks are tightening credit standards of commercial and industrial loans to small firms. Credit is tightening especially in commercial real estate and construction with close to 70% of banks tightening their standards. Thus, construction is likely to grind to a halt during the summer, the fall the latest. Moreover, close to 60% of banks are tightening lending standards for large firms and multifamily mortgages. Real estate sector will, almost certainly, be hit very hard.

If the U.S. does not fall into a recession during the fall (or possibly even during the summer), then it’s either a miracle or something major has happened in fiscal or monetary policy. Thus, like I, and we, have been forecasting for some time, the true magnitude of this crisis will, most likely, be revealed in the fall.

I urge you to keep preparing.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held responsible for errors or omissions in the data presented. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

Goetzmann, William N. (2017, p. 83-84). Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

Goetzmann, William N. (2017, p. 101). Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

Goetzmann, William N. (2017, p. 209-211). Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

Martin, Felix (2014, p.97-101). Money: The Unauthorized Biography.

This is an example of a prominent researcher of financial crises, Professor Gary B. Gorton.

What you think will be the best asset to be to prepare, gold, cash other commodities?