Quantitative easing and the fate of the financial system

QE -programs have made the financial system extremely fragile.

Currently, the most important thing, when one wants to understand the behaviour and the future of financial markets, is to understand the programs of quantitative easing, or QE.

They are asset purchase programs of the central banks and they have been running since late 2008 (with the Bank of Japan experimenting such programs from March 2001 till March 2006). In them the central bank buys (mostly) government bonds, but also corporate debt and sometimes even stocks. They have altered the financial system in a profound and a very dangerous way.

This is a pressing issue now when inflation has risen markedly, as tapering of QE -programs, where central banks end purchases of new assets, is likely to be the first action central bankers will take, when they start to rise interest rates. Quantitative tightening would be an effort of central banks to diminish their balance sheets. Such programs have a “cruel” history.

We dealt with the macroeconomic aspects of QE-programs in Q-Review 1/2018. In this newsletter, I'll explain their dynamics and the massive risks asset-purchase programs of central banks pose to the economy and the financial markets.

How does a QE -program work?

There’s an excellent blog, by a “Fed Guy” going through a QE -program step-by-step. I will only explain the critical details.

When a central bank buys assets through QE, it operates only through so called Primary Dealer banks which, however, are not often banks, but broker dealers. The central bank buys the assets, usually Treasuries, with newly created central bank reserves, which are ‘excess reserves’ to a bank. So, the central bank does not buy the assets with money, but with reserves, i.e., deposits at the central bank.

If the seller is a bank, it ends up holding the excess reserves (in exchange for the assets). However, if the seller of the asset is a non-bank, a corporation, a hedge fund, a pension fund, another trader, etc., the reserves end up to the central bank account of the bank of the non-bank. These will be balanced with a new deposits, which are owed to the non-bank.

So, QE:s programs force both excess reserves and well as new deposits into the banking system. These may have very different effects in the economy, as excess reserves flow only between financial institutions (banks), while new deposits are money entering the economy. Thus, to analyze the effects of QE-programs, we need to know from who does the central bank buy the assets?

Investors and household on the hook

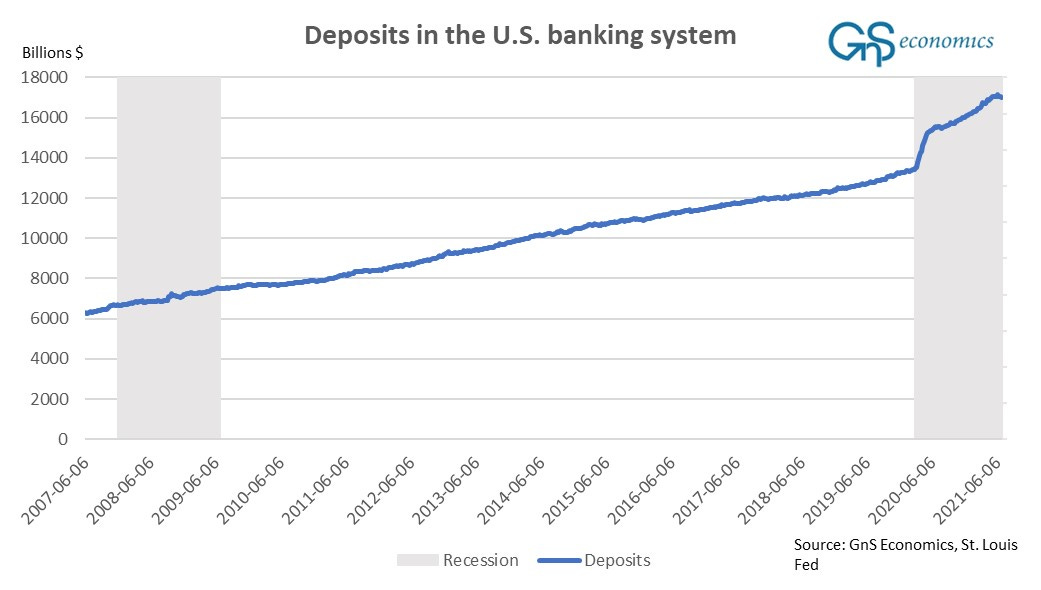

Seth Carpenter, Selva Demiral, Jane Ihrig and Elizabeth Kleea analyzed who sold the Treasuries to the Federal Reserve, the Fed, of the U.S. during QE1 and QE2 between November 2008 and December 2012. During that period, the Fed bought Treasuries mostly from households, including hedge funds, and pension funds. These are non-bank entities, which quite simply means that QE programs led to growth in deposits in the banking system.

During the ‘Corona bailout’ in the spring of 2020, the Fed extended its asset purchase programs to include a wide-variety of debt and bonds. If effectively backstopped “repo” and U.S. Treasury markets, intervened in corporate commercial-paper and municipal bond markets and short-term money-markets, and bought corporate bond ETFs, including some speculative-grade, or “junk” corporate debt.

As most of the assets the Fed acquired were held by non-bank entities, the renewed asset purchase programs lead to massive increase in the deposits in the U.S. banking system (see the Figure).

Forced lending

As QE-programs force excess reserces as well as deposits into the banking system, it disturbs the optimal portfolio allocation of banks. How do banks respond to this?

John Kandrac and Bernd Schlusche studied how QE:s affected the behaviour of banks. They found that excess reserves pushed into the balance sheets of banks led to higher total loan growth and increased risk taking. The way excess reserves led to this can be summarized as follows.

When banks are forced to hold the higher supply of reserves, their marginal bene fit will decrease. This creates a situation, where prices on various securities will be bid up, and banks respond to this by issuing additional loans until the marginal bene fit of the assets in banks' portfolios are restored to balance.

So, the QE program altered the net interest margins, the liquidity portfolio and the duration of the assets of the commercial banks, which induced the banks to increase lending and to move their portfolio towards riskier lending activities. As the amount of excess reserves grow, so does risky lending, until banks cannot lend anymore (I’ll return to this in forthcoming posts).

When banks are forced to issue more loans than they normally would, this ‘extra-lending’ is likely to go to riskier projects. Thus, QE:s make the banking system more riskier.

QE and the financial markets

We explained how QE affects the financial markets in detail in Q-Review 1/2018. Here are the main points.

In financial markets, quantitative easing leads to an excess liquidity environment. What this means is that when the central bank buys investment-grade bonds, it increases the liquidity (money) among private investors, which will lower the premium for illiquidity. The majority of this money starts to look for profitable investments. As the demand and thus the price for investment-grade assets are elevated, investors look for higher-yielding products such as equities.

Because there is a persistent buyer who is indifferent to rising prices and provides ample liquidity for private market participants, market volatility decreases which encourages investors to take even more risk. Since there is also effectively a ‘central bank put’, meaning that the central banks react to falling markets by increasing purchases, the investors get accustomed to the ‘buy and win’ strategies. This means that central banks guarantee market-wide profits. Machines (algorithms), passive investment funds and active investors get accustomed to this as well and engage in ‘buy the dip’ strategies every time the market falls. Complacency takes hold.

In addition, excess liquidity suppresses interest rates, which encourages investors to increased risk-taking through increased leverage.

Thus, QE:s lead to constantly increasing risk-taking in the financial markets by increasing the usage of leverage, through riskier banking lending activities and because investors move to riskier and riskier financial products. Moreover, as banks have been awashed with large quantities of excess reserves and ‘excess deposits’, the banking system has been saturated with the artificial liquidity (credit) from the central bank, which has spilled into the financial markets.

No wonder that stock markets are breaking all-time-highs, while yields of risky bonds of junk-rated companies are making all-time-lows (see my previous post). Alas, QE:s have pushed financial markets into speculative, central bank liquidity driven bubble, or “mania”.

Problems are brewing

Thus, what QE programs have “achieved” can be summarized as follows:

They have made the financial system more fragile.

They have made the banking system more fragile.

In a word, they have turned the financial system into a complete mess. Now, however, their road is ending, because the U.S. economy seems to be unable to cope with further excess reserves (I will return to this in more detail in coming weeks) and because the arrival of fast inflation, on which we warned in March, is likely to '“force the hand” of central bankers to tighten the monetary policy (to rise rates).

Moreover, we anticipate that the fast inflation will persist and create a need to taper, that is, to end purchases of new assets by the central bank. This means that the balance sheet of, for example, the Fed would cease to grow, the persistent buyer would become less persistent and the flow of central bank credit into the economy would diminish considerably.

It’s unlikely that the highly levered and speculative financial markets would be able to cope with rising interest rates and/or tapering. This would be even more so with quantitative tightening, or the shrinking of the balance sheet of central banks. I’ll return to this in more detail later.

In any case, things are getting interesting.