Issues discussed:

The collapse of the shadow banking sector leading into the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2007-2008.

The bailout of the financial sector.

The imminent aftermath of the GFC.

I will now continue the mini-series on the Great Financial Crisis. Earlier, I wrote that this would be a two-part series and that I would publish both entries during the Holidays. However, there will now be at least three entries. This second one got delayed just because of the work-load during the Holidays. My apologies.

I lived through the GFC as a PhD student at the University of Helsinki. It was the most intriguing time of my studies. Especially the fateful fall of 2008 taught me more about economics, and the financial system, than all my econ studies combined. That is why I told my students, e.g., during the euro-crisis (2012), an offspring of the GFC, to stop what they’re doing and follow the crisis.

In addition of being great teachers to economics students, financial crises are fearsome creatures bringing economic hardships and suffering. But they also shed light to things in our economies and financial systems that do not work and/or need improvement. If we heed those warnings, our economies will turn more robust, making us more wealthy. With the GFC this, most unfortunately, did not come to be. Most notably, the grip of authorities on our financial system, and economies, has become more and more pervasive ever since.

For quite some time, I lived under the fallacy that authorities were there to make our financial systems safer. Like I explained in the first entry, I don’t think this holds true anymore, regardless whether the motives of authorities are truly benevolent, or not. They mess up, and make things worse by trying to regulate more. I explained in the first entry, how mistakes and outright corruption of authorities were the main culprits why the GFC got so bad, and just recently authorities nurtured another crisis, the Global Financial Crisis of 2022- . Also this time around authorities, especially central bankers, over-did themselves, and we are yet to see the full costs of their indiscretion.

But, now to the main issue, i.e., how the Panic of 2008 proceeded and how it was handled? If you have not, I urge you to check the first part of the series before starting this.

Into the GFC

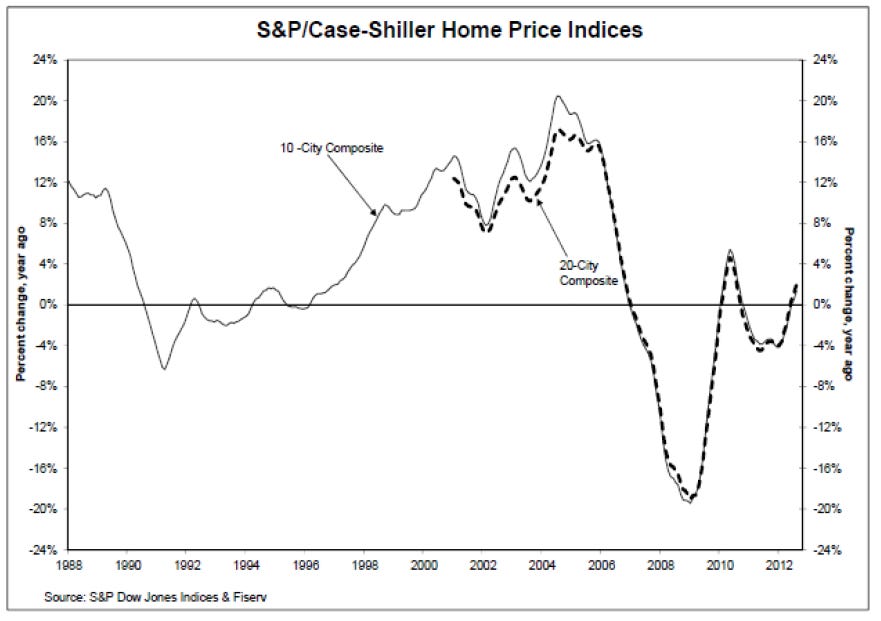

In late Spring of 2006, the US housing market boom started to sour. In early 2006, the interest free period of many mortgages ended. Prices started falter and then fall. Yet, they had accomplished a stellar rise. By 2006, according to the S&P Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price Index, prices had risen by astonishing 106 percentage points from 2000. From their peak in April 2006 to bottom in May 2009, prices dropped by 40 percentage points. It was a classical boom-and-bust cycle, but with exceptionally dire consequences.

Falling prices led to rapidly growing loan defaults almost immediately. Because the housing market had developed into an effective Ponzi, speculators (including ordinary households) were ‘under water’ very quickly. Their debt levels surpassed the falling value of houses and fire sales ensued. The narrative told prior the crisis that the U.S. housing market “would never fall” failed many. Entire areas of houses were abandoned, which led to further price decreases, to further defaults, to growing abandonment of houses and to further price decreases. A systematic, clustering cycle of price falls developed. Banks had assumed that the loan losses would not become systemic, but this was utterly broken by the clustering nature of the mortgage failures pushing the distribution of losses into "the tails" of the normal distribution assumed by the VaRs (see my previous entry).

The collapse

As mortgage failures mounted, so did losses inside CDOs. Their values started to waver. As CDOs were over-the-counter products, there was no public trading place and thus no public prices. Yet, rumors of falling values of CDO:s started to circle. Uncertainty set in.

The first mortgage issuer to go under, on January 3 2007, was Ownit Mortgage Solutions. First hints of he magnitude of the impending losses were revealed, when the High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Enhanced Leverage Fund linked to investment bank Bear Stearns failed in June 2007. The fund had a heavy exposure to subprime-mortgage-linked CDO:s, more precisely to bundled home loans from borrowers with weak credit histories (including NINJA loans). Bear Stearns was forced to bail out the fund on June 22, 2007.1

The next major player to get in trouble was German Deutsche Industriebank, or IKB. According to a statement given to a banker at J.P. Morgan from an official of the IKB, at the time they had "a lot of safe securities", but the investors were behaving "strangely". The bank was in trouble, because two of its investment vehicles (SIVs), Rhineland and Rhinebridge, were experiencing problems, while trying to sell their notes to investors in commercial paper markets. Funds had invested heavily on mortgage-linked CDOs and were funding themselves by selling their notes in the asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) market. Suddenly, investors did not want to accept their short-term debt obligations. IKB had also not put aside capital reserves for emergency credit lines for the funds, because the idea that the ACBP market would shutdown was considered inconceivable (regulators also did not require this; see the previous entry). Yet, it had happened. A consortium of banks bailed out the IKB on July 29, 2007.

While relatively small, these events marked the first signs of run in the commercial paper markets, where major corporations and institutions raised short-term funds for day-to-day operations. The market was considered so safe that even pension funds sometimes used it, and it acted like an alternative to bank deposits for big corporations. So, before the crisis, commercial paper market was considered as one of the safest (most liquid) corners of the capital markets, but investors were starting lose faith to the exotic US-mortgage-market-linked financial products, most notably CDOs, which had become a commonly used collateral there.

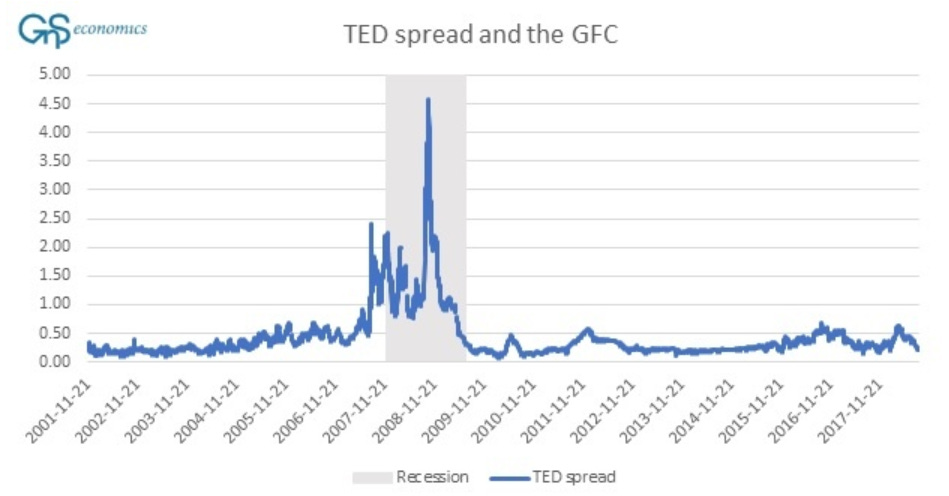

During the fall of 2007, stress in the inter-bank markets started to show. For example, the TED spread, presenting the difference between the three month US Treasury bill and the interest rate banks lend to each other in the inter-bank markets (Libor) exploded. Trust in the banking sector started to waver. A ‘silent run’ in the asset-backed commercial paper market formed.2

In early 2008, it became clear that also the values of some of the highest ranking (AAA) CDO -products would fall. In the repo-markets, where different financial institutions seek to fill their short-term liquidity needs, massive haircuts started to appear to subprime-related bonds and asset-backed securities used as collateral. Large withdrawals from dealer bank (prime brokerage) accounts followed. Suddenly, CDO:s were not accepted as collateral, while investors started to get wary on the CDO exposure of the counter-parties offering their paper in the financial markets. A run on the financial plumbing of the U.S. developed in commercial paper and repo -markets, as well as in prime brokerage balances.

Effectively, the financial markets lost faith on practically all mortgage-linked financial products. This led to a day of reckoning for the SPVs and SIVs. No one would buy their bonds. To make matters worse, the value of their collateral, which included a lot of AAA -rated CDO’s, crashed. Because demand for their revenues from commercial paper sales crashed and because tranche payments to investors kept on going, the business model of these off-balance sheet companies of banks failed. Losses mounted, collateral vanished and the "super-senior” risk, measured in hundreds of billions of dollars, started to find its way back to the balance sheets of banks. Moreover, many major banks, including Bear Stearns, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and Lehman Brothers had kept super-senior risk in their books, while insuring it through an outside party (see the previous entry). The risk that should have been negligible (mathematically) realized in gargantuan quantities.

The insurers of the super-senior risk, like AIG, witnessed a deluge of claims (remember also that banks were not obliged to reserve any collateral to loans they provided to SIV:s and their ilk). Many banks also had acquired AAA -rated CDO:s as collateral. Thus, their income streams (from CDO’s) dried up, super-senior losses mounted, while their off-balance sheet companies failed, leaving banks to hold the ‘ball’ (toxic assets + loan losses). Trust evaporated, the inter-bank market froze over and the financial system started to grind to a halt.

The Bailout

Lessons of the Great Depression had clearly been learned, and when the crisis hit, the global leaders sprang into action led by the eminent scholar of Great Depression and then the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke. After the failure of the investment bank Lehman Brothers on September 15th, 2008, the Fed first extended the range of securities it accepted as collateral for its loans. It also extended a bridge loan to the insurance giant AIG, who had provided CDS's for majority of the super-senior risk.

On September 19th, the US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson outlined the Troubled Assets Relief Program, or TARP, aimed at recapitalizing the banks by purchasing mortgage related assets from them. It was first voted down by the U.S. Congress on the 29th of September and accepted on the 1st of October, after mayhem gripped the financial markets. First funds were paid on the 14th of October.

During the first week of October 2008, the DJIA fell by 22.1 percent, FTSE by 21.1 percent and Tokyo Nikkei index by 24.3 percent. There was a threat of a systemic meltdown, where financial system seizes to function. There was genuine apprehension that major global banks would not open their doors on Monday the 13th October. However, on Sunday and Monday night, the leaders of the G-7 industrialized nations hammered-out a comprehensive rescue package for banks.3 It included borrowing guarantees, recapitalization of banks and liquidity support from major central banks. On Monday, banks opened their door normally and credit kept flowing, although in diminished quantities.

The Federal Reserve also extended its operations by creating new innovative ways to ensure dollar liquidity. It created liquidity-swap operation to carefully selected core central banks across the globe, so that they could provide dollar credit on demand on the ailing domestic financial institutions. On October 7th, the Fed started to accept commercial paper as collateral, effectively guaranteeing the market worth around $2.4 trillion. In late November 2008, the Fed announced it would start buying the debt of Government Sponsored Enterprises (“GSE”) and mortgage-related securities from the secondary markets.

SIV:s and other shadow banks created a perplexing problem for authorities. They sat outside the balance sheets of banks, which meant that federal authorities had no mandate to intervene. However, as the crisis intensified, it became clear that the shadow and commercial banking sectors were so entwined that also the off-balance sheet vehicles began to fall under government jurisdiction. In April 2009, the Financial Accounting Standards Board relaxed the FAS 157 rule, which gave banks more leeway in determining the (non-market) value of their exotic financial products. It effectively allowed banks to pretend that CDO:s had kept their purchasing value. This was something of a financial fraud, but it was an easier and politically more acceptable option than a painful re-structuring of the global banking system. This action led to serious repercussions, including zombification, which I go through in the third installment. The IMF issued several emergency loans to countries across the globe. Towards the end of the year, the crisis starts to ease, but bank bailouts and failures continued till 2010, and further.

During the crisis, a pivotal moment for the future arrived on March 18th, 2009, when the Fed extended its asset purchase program to include U.S. Treasuries. These became known as the programs of quantitative easing or QE, and they never ended. I return to these in more detail in the third installment.

Conclusion: Global recession

The GFC pushed the global economy into a recession. Due to the cascading bank failures and problems across the globe, global liquidity dried up. Gross capital flows plunged by 90 percent from 2007 to 2008. The global banking system lost over half of their regulatory Tier-1 (regulatory) capital. The total amount of write downs of financial assets and loans were over $2.2 trillion, close to four percent of global GDP (in 2010). To worst hit countries, the UK and the US, the total costs accounted over nine and over six percent of GDP. The crisis took the biggest toll in a small Nordic country, Iceland, whose whole banking system collapsed.

However, the GFC was quickly contained through the bailout of the financial system issued by the Fed and G-7 countries. The comparison between the Great Depression and the GFC gives some indication on the quick turnaround. While close to 10 thousand banks (around 40% of the total) failed during the Great Depression in the US, just over 250 banks (around 3% of the total) failed during the GFC. During the Great Depression, bank failures in the US were scattered over a period of six years, while in GFC most of the bank failures occurred within two years. During the Great Depression, the real GDP per capita of the G7 fell by 18 percent. During the GFC, it fell by around five percent.

The GFC also led to another major crisis, known as the European debt crisis. I’ll return also to this in the third installment.

Dates and historical accounts are from Gillian Tett’s Fool’s Gold, from Johan Lybeck’s A Global History of the Financial Crash of 2007-2010, and from Gary B. Gorton’s Misunderstanding Financial Crises.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held responsible for errors or omissions in the data presented. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

Bear Stearns was sold to J.P. Morgan just nine months later (16 March, 20087) in an effective bailout with the Federal Reserve ‘ring-fencing’ much of the losses of Bear.

A “standard” or “historical” bank run is one, where people queue outside banks to raise cash. “Silent run” occurs through account transfers and sales of bonds and stocks in digital form.

The leading industrialized nations: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US.

Greenspan never tightened and Bernanke never eased. The money stock can never be properly managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit.

Please expound on how the market started to "sour" :

"In late Spring of 2006, the US housing market boom started to sour"