Issues contributed:

Credit recession is deepening in the U.S.

The private sector has, most likely, already entered a recession.

The likelihood of a second wave of the banking crisis grows rapidly.

In a recent interview Stanley Druckenmiller, a billionaire investor, blasted the administration of President Biden for recklessness and “spending like we would still be in Great Depression”. I wholeheartedly agree.

In 2023, the fiscal deficit of the U.S. government was sobering 6.3%, while during the Great Depression of the 1930s, federal government run a deficit of around the similar magnitude . The only difference was that between 1929 and 1934, over 9800 banks (nearly 40% of the total) failed, industrial output fell by 52%, whole sale prices by 38% and real income by 35%, and at its peak over 24% of the total work force were unemployed. Currently, the U.S. unemployment stands at 3.9%.

Why is the Biden administration running such ludicrous deficits? They are most likely doing it to mask an U.S. recession, which has now started. Let’s take a closer look.

Credit recession

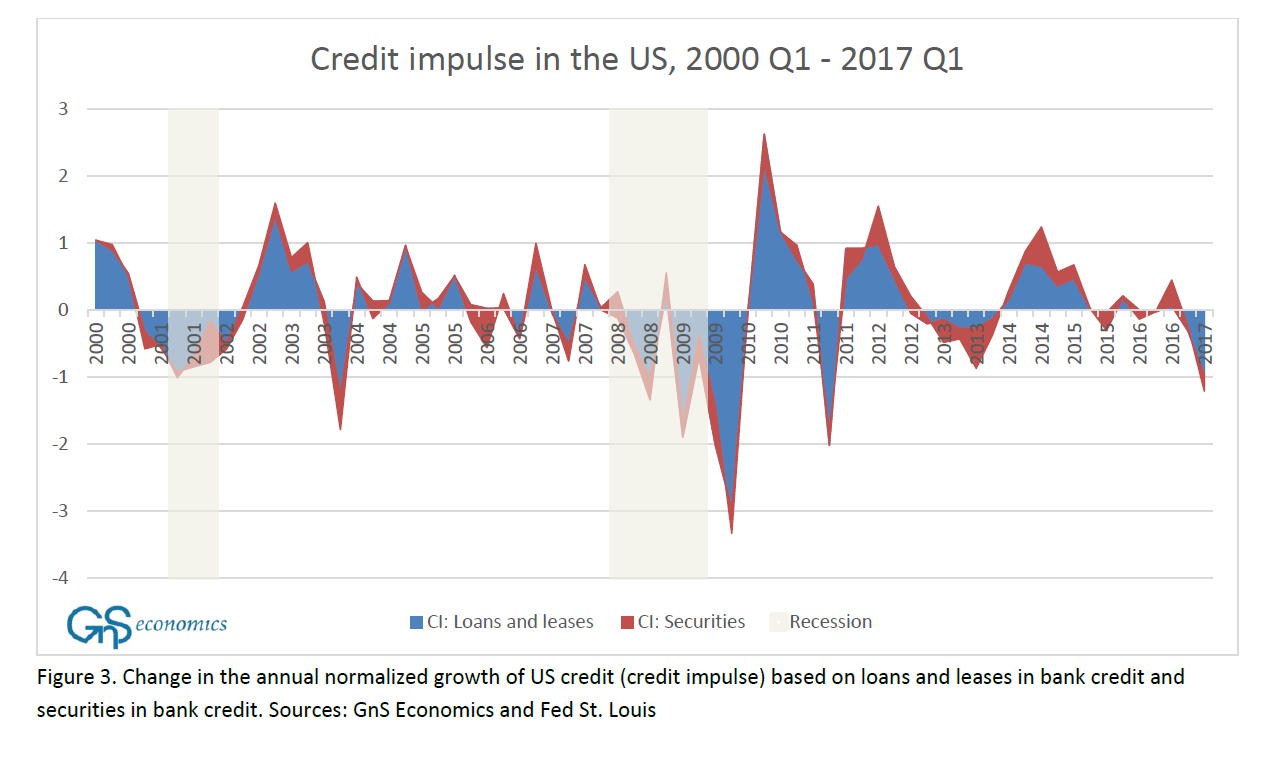

I, and we at GnS Economics, have been tracking the credit creation of U.S. banks for a while. Already in 2017, we used the credit impulses in an effort to assess,1 where the U.S. economy would be heading.

However, we soon discovered that the forecasting ability of these “impulses” was weak. They were just too volatile and thus the forward-looking information they gave was full of statistical noise.2 Thus, we disregarded them.

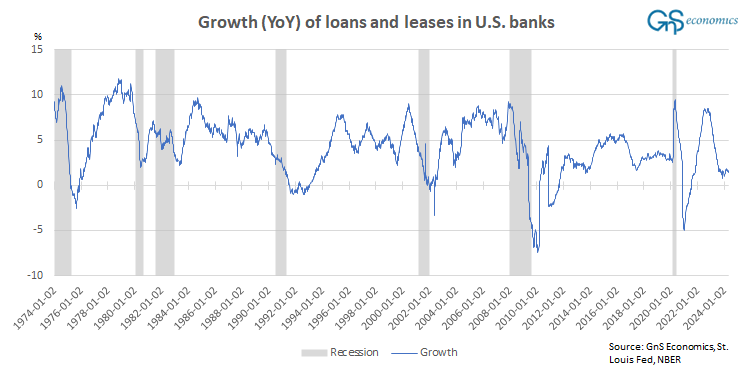

If we observe, for example, the annual growth rate of loans and leases in bank credit (loans and leases given out by commercial banks), it seems much more informative.

What the figure above informs us is that the annual growth rate of loans and leases declines strongly only at the end or after a recession, when consumers and businesses cut back their spending and thus borrowing. What we also observe is that loan growth is currently at levels not seen outside recessions, or right after them. This means that the U.S. is effectively in a credit recession, like I explained in early April, but there’s more.

Private sector recession

The next figure presents the monthly, year-over-year growth of commercial and industrial (C&I) loans given out by U.S. commercial banks. I have marked the months, when C&I loan growth has fallen to negative.

You notice immediately that the growth of C&I loans has fallen to negative only during or right after a recession (with the exception of the self-made recession in 2020 and the subsequent “recovery”). Like I explained in early April, While credit markets provide a hefty share of overall corporate funding in the U.S., small and medium sized corporations (SMEs) rely heavily on bank lending in their funding needs. This implies that normally a recession starts, when SMEs start to cut back their consumption and/or investments. This is where the growth of C&I loans ‘leads’ the business cycle. However, some recession, like the one that commenced in 1973 (oil shock) and 2007 (financial crisis), are product of a shock, which pushes consumer and business to cut back their consumption (to goods and services and/or capital goods). With these recessions, the C&I loan growth ‘lags’, as it drops only after businesses cut back their spending (borrowing) and/or go bankrupt.

Currently, C&I loan growth fell into negative in October. Never in the history of the series has it fallen to negative without the U.S. economy being in a recession or recovering from one. We can rather safely assume that it will not be different this time around.

One rarely used indicator, which relates to this, is the private sector yield curve. It measures the difference between the long-term corporate bond yields and the bank prime rate.3 The bank prime rate, reported by the 25 largest (by assets in domestic offices) FDIC-insured U.S.-chartered commercial banks, is the underlying rate for most credit card, auto, housing, and short-term business loans.

Effectively, the private sector YC measures the difference between the rates which SMEs and large corporations borrow. When it inverts, it signals that SMEs are paying more for their bank loans than big corporations are paying for their loans acquired through the capital markets. This implies that banks are tightening their lending standards and/or that the central bank is rising interest rates, which lead SMEs to cut back their borrowing and thus consumption, pushing the economy into a recession.

While the track record of private sector YC is no impeccable (see, e.g., the late 1990s), it has provided a fairly accurate forward-looking information (pre-warning) on recessions. Moreover, it’s not directly affected by the Fed buying and selling of Treasuries, like the traditional yield curve. The private sector YC has been inverted since late-July 2022 when, for example, the 10y/3mo YC inverted in October 2022. Private sector YC thus currently strongly signals onset of a recession.

To emphasize the point of the credit data, optimism of small businesses in the U.S. has fallen below lows of 2020 lockdowns. Most notably, it collapsed during 2022 and has never recovered. This is a clear recessionary signal.

Conclusions

To add one more indicator, The Kansas City Federal Reserve National Labor Market Index, LMCI, declined sharply in April following a trending decline over the past two years. The index has never seen such a decline without a recession.

I, and we at GnS Economics, have been slowly building our understanding on the current drivers of the U.S. economy. We have especially pondered the factors that have kept the economy afloat despite of the rapid interest rate rises by the Federal Reserve and matured economy. In February 2023, we identified ‘excess savings’ as the main force carrying the U.S. economy “for a while longer”. Now, for example, sharp rise in credit card, auto loan and mortgage delinquencies hint that consumers are scraping the ‘bottom of barrel’, i.e., that they have run out of their “excess” money. The only thing carrying the economy is thus the manic and utterly irresponsible fiscal stimulus by the Biden administration. Yet, even it cannot save the economic momentum of the U.S., when consumers and businesses ebb, which I think has now occurred.

The U.S. credit data shows that SMEs have, and are, strongly cutting bank borrowing. Considering this, and their declining optimism and deteriorating job market, it’s really difficult to come to any other conclusion than that the U.S. is entering a recession. We are at the end of the fiscal clownshow administrated by the Biden administration.

This also implies that the likelihood of a second (third in Europe) wave of the banking crisis will start to grow rapidly now. Take heed.

Paywall removed on 8/22/2024. Erratas corrected on 3/28/2025.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held responsible for errors or omissions in the data presented. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

The credit impulse, or the flow of credit argument was presented by Biggs, Mayer and Pick (2010). They argue that in cases where domestic demand is credit financed, GDP will be a function of new borrowing, measured as the flow of credit. This applies especially to recovery periods, where the stock of credit is usually depressed, but it is also shown to react to downturns earlier than the growth of credit. This is most likely related to the fact that new borrowing, or the credit impulse, is more likely to reveal a turning point in the trend of debt stock, when it is either low (recession) or high (end of an expansion).

We used a standard way to calculate the credit impulse, which consists of analyzing the GDP normalized growth rate of credit over a period of a year. Formally:

I’ve studied stochastic time series, i.e. time series driven by random shocks or trends, for 20 years. In my thinking, the problem of credit impulses is that it mixes two series (gross domestic product and credit) that are strongly affected by random shocks. This implies that their combined series inhibits a high level of stochasticity (“noise”), which shows up as heavy volatility. This implies that the ability of credit impulses to forecast the economy is likely to be poor.

Here I use the Baa -rated corporate bond yields with a maturity of 20 years or more.